Megalong Books invites history buffs and students and teachers to an afternoon at Katoomba Falls Kiosk with Katoomba local Dr Naomi Parry and Sydney University’s Professor Stephen Garton, two of the four authors of a New South Wales and the Great War, a new book that Governor David Hurley called “visually arresting and authoritative account of NSW during and after the Great War”.

Megalong Books invites history buffs and students and teachers to an afternoon at Katoomba Falls Kiosk with Katoomba local Dr Naomi Parry and Sydney University’s Professor Stephen Garton, two of the four authors of a New South Wales and the Great War, a new book that Governor David Hurley called “visually arresting and authoritative account of NSW during and after the Great War”.

When the Great War began in August 1914, the people of New South Wales took up the call to arms. NSW sent more people than any other state to serve overseas and many more worked and volunteered to support the war effort. But the economic, political and emotional strains of war, and the loss of so many young men, and some women, in the service of their country, fanned social and political divisions and wrought lasting changes to the society to which serving men and women would return.

New South Wales and the Great War tells this story. It is drawn from the rich visual and written records held by the Anzac Memorial, the State Library of NSW, NSW State Records, the NSW Department of Education and the University of Sydney, as well as collections from Bourke to Gilgandra and Newcastle to Lithgow.

It is the official publication of the NSW Centenary of Anzac Advisory Committee and over summer it was distributed, free of charge, to all public and Catholic schools in New South Wales and to most libraries.

This event is an opportunity to meet the authors and the publisher learn about the writing of this important publication.

Venue: Katoomba Falls Kiosk, Cliff Drive, Katoomba

Date: Sunday 30 April 2017

Time: 2-4pm

Entry by gold coin donation.

Megalong Books will be selling copies on the day.

All posts by Naomi Parry

A decade

Today is the tenth anniversary of the submission of my PhD thesis, ‘”Such a longing”: black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880 to 1940’. I graduated in September 2007, after a revision or two. I’ve had a pretty good run since then – a couple of years as a project officer, a couple as a cultural development officer, three wonderful years as a research fellow on the Find & Connect web resource, before heading to the Dictionary of Sydney and writing New South Wales and the Great War. And now I’ve come back to the substance of my PhD, in a way, working as a senior policy officer at the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse.

Today is the tenth anniversary of the submission of my PhD thesis, ‘”Such a longing”: black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880 to 1940’. I graduated in September 2007, after a revision or two. I’ve had a pretty good run since then – a couple of years as a project officer, a couple as a cultural development officer, three wonderful years as a research fellow on the Find & Connect web resource, before heading to the Dictionary of Sydney and writing New South Wales and the Great War. And now I’ve come back to the substance of my PhD, in a way, working as a senior policy officer at the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse.

Workwise, it’s all been good and I’m pretty happy with that particular life choice. My son was born 18 months after I started my PhD, which I don’t really recommend, although he is the best thing I’ve ever done. Once when he was four and tucking him into bed he told me he wanted to stay up to help me write my PhD. It seemed like it would take forever and it did because he was six before I was done with it. Now, of course, he’s six foot two. Ten years. Wow.

1967 in Tasmania

I’ve just come back from Tasmania, my home country. Today is 50 years since the 1967 bushfires, which devastated southern Tasmania. More than 60 people died. The Huon and Channel were also devastated and the town of Snug ravaged, leaving many dead. The fires raged so hard in the foothills of Mt Wellington that authorities contemplated setting off a line of explosives across West Hobart to stop them penetrating into the CBD.

Big fires leave scars. I wrote this in 2015, in an essay I contributed to Dee Michell, JZ Wilson and Verity Archer’s Bread and Roses: Voices of Australian Academics from the Working Class:

We arrived in 1974, at a time when there was little reason to hope in the valley. At intervals in the green rolling hills you could see ash-coloured chimneys, twirled with sheets of whitened corrugated iron and bed springs, marking places where people had lived before the 1967 bushfires, but were too scared or dead to return and clean up. The deaths spooked me as a kid. Tales of people who had hidden in water tanks and boiled had a horrible relevance when you heard that the fires had touched the very corner of your new bedroom. It is only as an adult that I’ve come to appreciate the economic loss that went with those other, profound losses.

There’s a Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery exhibition on at the moment that talks about it, and some brilliant ABC Tasmania and LINC photo galleries that really show how awful it was. As climate change intensifies, we could all face this. I really hope we don’t.

Dr Naomi Parry, MPHA

I just got news that I’ve been accredited as a professional historian by the Professional Historians’ Association of NSW & ACT. This means I can add another set of letters after my name: MPHA.

It’s very exciting to be accepted as a peer by a bunch of historians I respect. On a more personal level, way back when I was a baby heritage practitioner, just after I arrived in Sydney, I worked with some fabulous professional historians. I used to wonder how they got their jobs and now I guess I know.

I feel both grown up and rejuvenated.

Writing community and personal history: Part I

The work I am doing right now is mostly editing, in one form or another, so I am spending my days taking the words of others and turning them over and over, to remove the mistakes we all make as we write, and present a polished product. This is proofreading and we all need it, no matter what we are writing, because when we are working so hard to get content across we can no longer see the mistakes we have made; a date here, a silly word choice there, a disastrous error of grammar. It’s simple and straightforward work, very enjoyable, and mostly appreciated by the person being edited.

Other times, one has to be interventionist. Sometimes fact-checking is needed and other times the work has to be cut so hard it must be rewritten. When I am doing this I am obliged to identify what in the piece is not working, why that is, and the words that might work better. It is an intense and reflective process, and that reflection generates plenty of ideas about exactly what it is that makes good (and bad) history. (I then have to sensitively and kindly explain to the person being edited why I have done what I have done, and sometimes they are upset, and my reflections are necessary to win them over, or at least persuade them to accept it).

When I say I am reflecting on history, I’m not talking about a philosophy of history, or even a philosophy of writing. I certainly can’t talk about history in the way that Tom Griffiths and his subjects do in The Art of Time Travel. The down-and-dirty work of editing requires a narrower focus. Narrow doesn’t mean shallow though, because good history writing requires deep thought and a great deal of integrity, as well as commitment to the reader, and to the story.

My PhD supervisor knew that I thought most community history was deathly boring, and used to accuse me of writing it when I had produced something leaden. It got me thinking, and now I edit so much of it, I have to think more. So, a few insights from recent voyages in editing, and some general points from a long career reading community history.

When writing history

- What matters is the story, so find it. Don’t tell us it is remarkable or important or tragic; show us that it was by setting the context.

- Don’t do “this happened and then, and then, and then” history. Think in themes, not chronologies. Don’t be afraid to start your story somewhere other than in the beginning.

- Never say “something was done”. Always tell us who did it. This is called writing in the active voice but it’s not just a grammar technique. Explaining who did what to whom puts the energy, heart and meaning into your story. The mine did not close. The government closed the mine. The workers were not sacked. The boss sacked them.

- Never try to put yourself into people’s minds or insert thoughts in their heads or words in their mouths. Focus only on what they said, and what you can know about what they did. If they said one thing and did another, point that out, but never say “they must have thought …”

When writing (even a short) biography

- Don’t tell us they were important/remarkable/amazing. Show us they were, by setting them in context and framing the times they lived in and their place within them.

- You are writing about a person, so write about their personal life and their personality. It matters. This is particularly important from a feminist/other point of view. It’s important to ask not only how a subject’s personal life affected their actions and emotional wellbeing and capacities. It matters and we need to ask these fundamental questions about women and men.

- Ask yourself in what ways your subject was awful and why they were like that (without putting your words into their mouths). Be really honest about these things and about how they shaped the person’s life and actions.

- Then, ask yourself why you like them and be honest about that. Remember, you have an agenda too. What is it?

When writing history in Australia

- Don’t forget this is Aboriginal land. Always was, always will be. Find out about the people whose land it was and is.

- And, because of this, every single person who has come here since 1788 was a migrant. You can think of them in waves: Anglo-Irish, Europeans, Chinese, post-war displaced persons, Indo-Chinese, etc, but you must always think of migration as a continuum. We are a migrant country.

And finally, be kind to your reader. They don’t always know what you know, so make sure you give them a few words that will help them understand just why the cool thing you are telling them is so very cool.

Then, when you are finished, give it to a nice editor and let them knock those rough edges off, and hope your readers enjoy it.

New South Wales and the Great War is launched, and for sale!

New South Wales and the Great War was launched by His Excellency General The Honourable David Hurley AC DSC (Ret’d), Governor of New South Wales, at Government House on 9 November 2016. He was very kind about it and his speech is here. It was rather amazing to sit there and listen (intently) while our book took on a life of its own.

The book was a headline project for the New South Wales Centenary of Anzac Committee, and their press release is here. Proceeds will go towards the Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park. You can also buy it from the State Library’s online bookshop and from Gleebooks for $35.

New South Wales and the Great War

I have received an advance copy of this, my first book, and I am pleased to say it’s going to be launched by the Governor of New South Wales, The Honourable David Hurley AC DSC (Ret’d), at Government House on 9 November 2016, with Lieutenant General Kenneth James “Ken” Gillespie AC, DSC, CSM, who is the chair of the NSW Centenary of Anzac Committee. I and my co-authors, Brad Manera, Will Davies and Stephen Garton, will all be signing copies in advance and the book will be sold through Dymocks.

I have received an advance copy of this, my first book, and I am pleased to say it’s going to be launched by the Governor of New South Wales, The Honourable David Hurley AC DSC (Ret’d), at Government House on 9 November 2016, with Lieutenant General Kenneth James “Ken” Gillespie AC, DSC, CSM, who is the chair of the NSW Centenary of Anzac Committee. I and my co-authors, Brad Manera, Will Davies and Stephen Garton, will all be signing copies in advance and the book will be sold through Dymocks.

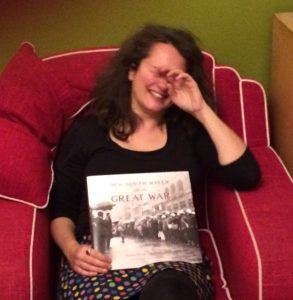

On a more personal note, here’s some images of a historian getting her first book in her hands.

Vale Inga Clendinnen

A writer who taught me that there is so much more to exploring history and the self than what is in the academy. I have never felt so giddy as I did when I got to hold her hands when she won the Premier’s Literary Awards for Dancing with Strangers. That book, which I return to again and again, I loved for showing me new sides to material I already thought I knew. Here is Text’s obituary. https://www.textpublishing.com.au/blog/vale-inga-clendinnen

Open letter to Turnbull and Dutton about asylum seekers

Dear Minister Dutton and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull,

I am a historian who has spent nearly two decades studying the history of child welfare in this country. My PhD ‘“Such a longing”: the treatment of black and white children in welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880-1940’ (UNSW History, 2007) was written while the previous Liberal government asserted that the treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were separated from their families was in accordance with the welfare standards of the time. In 2008 the Parliament of Australia, with the support of Malcolm Turnbull as leader of the opposition, reversed that position and apologised to the Stolen Generations for what had been done to them. Since then, the Parliament has apologised to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants and to those affected by Forced Adoptions. In each of the three apologies the stakeholders have felt they were supported by Malcolm Turnbull – I know this, because I spent three years working with those stakeholders as part of the team which put together the Australian Government’s Find & Connect web resource.

As the conditions for detained asylum-seekers on Nauru and Manus Island deteriorate I am moved to remind you both that the damage being done in your names will have a high cost. The adults you have detained there are suffering and so are their children. Small children and babies. Our own very recent history shows us that this sort of ill-treatment wreaks havoc on the current generation and their descendants, leaving very real scars on the people affected. The shame for our own community is incalculable and you should not be doing this in my name.

I would like you both to answer the following questions to ensure immediate improvement in the lives of people on Nauru and Manus Island:

1. What will you do to ensure that medical attention, to Australian standards, is available at Nauru and Manus Island (or that speedy evacuation systems are in place)?

2. What will you do to ensure women and babies receive Australian-standard prenatal, post-natal and infant welfare care?

3. What will you do to ensure Australian-standards of child protection are in place on both Nauru and Manus Island and when will you do it?

4. How and when will you improve security for asylum-seekers on both Nauru and Manus Island?

Finally, when will you resettle people found to be refugees from both Nauru and Manus Island?

I would appreciate a prompt answer to these questions. Please do not write back saying that this is the responsibility of the PNG or Nauru governments. You are party to contracts with these governments and you remain responsible for this situation.

Sincerely, Dr Naomi Parry

The end of a working class pastime

Working class pastimes are always complicated, aren’t they? Gambling, in all its forms, is destructive, whether it’s cards or betting. Ancient “sports” like cockfighting, dog-fighting, bull-baiting and bare-knuckle fighting have all been so brutal they have been banned in English-speaking countries. Then again, “sports” favoured by the upper-classes, such as horse-racing and the betting associated with it, have been heavily regulated to standards of what some consider to be safety.

Greyhound racing in Australia arose from the ancient practice of coursing, which involved setting fast hounds in pursuit of small prey. Scratching Sydney’s Surface has a great piece about the origins of coursing, which I drew on when I wrote about Lithgow Greyhound Racing Track for Lithgow History Avenue. The electrified greyhound racing track (the tin hare), which we now know as part of the sport now, was introduced in the late 1920s and both reduced the (public) cruelty of the activity and increased its popular appeal. Greyhound racing was accessible, low-cost (compared to horses) and became part of the fabric of many working class communities. There was many a working class household with a racing dog in its backyard.

And now, with Mike Baird announcing the banning of greyhound racing, it’s all gone. On the one hand, too many dogs live intolerable lives, too many small furry creatures are sacrificed and too many beautiful greyhounds die horribly. But it’s another element of working class life that is biting the dust, taking much that is positive with it.

And what will become of those hounds? They won’t all be converted to pets or rehomed. It’s a big change. Necessary, but big.